Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Point Sparring

Many martial artists involved in tournament competition incorrectly interchange the terms “sparring” and “fighting”. This can be a dangerous practice since sparring is very different from fighting, and in some cases the improvement of one’s sparring skills can actually be a detriment to one’s self-defense skills. The reason for this is that there are certain techniques that are deemed “illegal” in sparring, such as groin and knee kicks, and excessive head contact. The reason that these techniques are not acceptable in sparring is due to the fact that they can be very dangerous, which is exactly the reason that they are so effective in extreme self-defense situations. The truth is that “the tournament [competitor] doesn’t have to cope with reality.” [1] Tournament competitors who train to hone their sparring skills and remove “illegal” techniques from their personal arsenals in favor of more effective point-scoring techniques are not going to be able to call on these techniques to protect themselves on the street.

“In sport karate, the emphasis is on speed, not focus, and the techniques are often not valid; it’s all who can touch first. Tournament techniques are designed for one thing: scoring points. Therefore students are being rewarded for executing invalid martial arts techniques.” [2]

Self-Defense and Legal Implications

“When martial arts become sports, they emphasis techniques that are inappropriate for a self-defense situation. Often, someone who trains in self-defense will hesitate while his mind is attempting to adapt his martial arts repertoire to the rules of a point tournament. But this is far less dangerous than the tournament [competitor] who doesn’t understand the need to protect his knees or groin because he has been working within an environment that doesn’t stress such protection. It’s been said ‘As you train, so will you react.’ Anything which creates confusion in the mind of the practitioner causes a barrier between thought and action.” [2] Effective self-defense is not the ability to beat somebody up, rather it is the ability to avoid getting hurt yourself. A competitor’s mindset is often to strike first in order to score, which is actually contrary to the tenet that martial arts is for defense only. This approach is more likely to start fights than it is to end them, and even if you only get one bruise, it’s one bruise more than was necessary if the fight could have been avoided. “Real fights are only the ones you cannot avoid. Those are the only fights in which you’re in real danger.” [3] “If you can avoid a fight, you have conquered the situation. You have achieved victory.” [4]

“The ‘first-strike’ attitude of the [tournament competitor] goes against the ethics of most martial arts. On the street, a martial artist shouldn’t strike without provocation, yet sport karate forces the competitor to do so. This creates an aggressive, competitive, must-win mentality. In other words, in self-defense, if no one hits, everyone wins; in sport karate, if no one hits, no one wins.” [2] This problem also has legal implications as well. “The truth is that you stand a reasonable chance of facing criminal penalties for defending yourself using the knowledge you learn from the martial arts. For you to make a successful claim of self-defense, you must convince the police, judge or jury that you reasonably believed that you were in imminent danger of bodily harm from an unlawful attack by the assailant that you used only the force necessary to neutralize the threat. So in effect the burden of proof shifts from the prosecution to the defendant in cases of self-defense.” [5]

Benefits of Sparring

This is not to be interpreted as a case against sparring; on the contrary, sparring can be a useful tool, if done properly. Consider this analogy: Sparring can be to self-defense what skating is to ice hockey. Clearly skating is a crucial foundation skill for a hockey player to possess, but the ability to play effective hockey goes well beyond the ability to skate. Sparring can be used to improve balance, timing, distancing, reaction time, stamina, and many other qualities that an effective martial artist must posses. However, if these foundation skills are not built upon concurrent self-defense training, then they will not be useful for personal protection. In any event, “the role of modern martial arts training should be to improve the quality of a practitioner’s life, not fashion him into a lethal weapon.” [6]

---------------------

[1] Wong, Scott “Genghis”. “The Theoretical Martial Artist.” Martial Arts Training. September, 1993: 28-29, 70.

[2] Meyer, Lynn. “Can Sport Karate Ruin Your Self-Defense Skills.” Black Belt. November, 1989: 46-59.

[3] Blaur, Tony. “Where Do You Stand?” Martial Arts Training. May 1997: 45.

[4] Nardi, Thomas J. “Winning or Victory.” Martial Arts Training. July, 1993: 56-57.

[5] Bishop, James. “Guilty or Not Guilty?” Black Belt. February, 1999: 174-179.

[6] Plott, Michael J. “The 10 Dumbest Statements Martial Artists Make.” Black Belt. February, 1997.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

The Purpose of Stances

While stances are an extremely important part of martial arts training; stances in and of themselves have no function. The purpose of a stance is to provide a suitable foundation from which techniques can be executed. Without a proper stance, a martial artist would have ineffective techniques, be they slow, off balance, or what have you; or would be unprepared for an incoming attack. For many tournament competitors, stances are more a way of answering the question, “How low can you go?” This approach to stances, while is may show strength and muscle control, does not show a true understanding of the purpose martial art stances should serve.

In Martial Arts Training interviews with Richard Branden and Suzann Kay Wancket, both of these tournament competitors stress the importance of leg strength, but fail to make the connection between deep stances and martial arts, other than their experience in the ring. “The great warrior Miyamoto Musashi once wrote, ‘Make your fighting stance your everyday stance, and make your everyday stance your fighting stance.’” [1] If Branden and Wancket were to take the advice of the man considered the greatest swordsman in history, they would either have to stand around in a stance so low as to be ineffective, or raise their stances to a natural level that will to allow them to be effective in a self-defense situation.

The insistence of low stances, knowing that they make reacting in a self-defense situation impossible, is an indicator that forms competitions are more about difficulty than effectiveness. Maybe someday a competitor will bow in and start singing “I am the very model of a modern major general” from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance, a difficult song and probably as irrelevant to martial arts as low stances. Difficulty isn’t relevant in the real world, especially since the simplest techniques are undoubtedly the most effective. The same is true of stances.

---------------------

[1] Blaur, Tony. “Where Do You Stand?” Martial Arts Training. May 1997: 45.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Martial Arts Forms

“For some, they are an antiquated training method with little practical value for the contemporary martial artist. To others, they are the heart and soul of an art. What are they? Forms.” [1] The exact origins of martial arts forms is usually a topic of debate, but in the case of Okinawan Karate styles it’s believed that kata originated “when Japan occupied and controlled most of Okinawa’s territories in 1609, the samuari took away the Okinawans’ weapons. As a result, the Okinawans had to find another way to protect themselves.” [2] Since the Japanese also forbade training in the fighting arts, the Okinawans devised ways to practice self-defense that, on first glance, would resemble harmless exercise or dance.

Kata, tul, hyung, or whatever a martial art calls them according to their traditions and country of origin are the cornerstone of martial arts training. Most forms have some sort of historical or cultural significance to the name. For example, the Taekwon-Do form “Yul-Gok is the pseudonym of the great philosopher and scholar Yi I (1536-1584) nicknamed the ‘Confucius of Korea.’ The 38 movements of this pattern refer to his birthplace on the 38` latitude and the diagram [of the pattern] (~) represents scholar.” [3]

Clearly, these forms mean much more than just punches and kicks. “If you don’t learn any history, you will have no grasp of the concept of your martial art.” [4] To reinforce this point, I have heard Taekwon-Do Grandmaster Sun Duk Choi state that one cannot train in Taekwon-Do without also studying Korean history. Furthermore, forms are “the most vital method of transmitting or learning a skill in the budo.” [5] It is this type of training that is absent when students are lead to believe that their forms are “good” or “bad” based on the subjective opinions of others during one particular performance. Forms get reduced to the superficial, how they look, instead of what really matters.

Even tournament competitor Jon Valera said that “forms are supposed to be a fight scene.” [6] However, it is inconceivable that any of the carefully rehearsed flying and spinning kicks that made him successful in a tournament would be successful in a street fight, “a synonym for absolute chaos.” [7]

---------------------

[1] Nardi, Thomas J. “Love ‘Em or Hate ‘Em.” Martial Arts Training. July, 1998: 20.

[2] Blumenthal, Paris. “Traditionalism is Here to Stay.” Martial Arts Training. May 1998: 37.

[3] International on-Do Federation. “The Interpretation of Patterns.” http://www.itf-taekwondo.com. 1999.

[4] Barber, Clayton. “Brain Washing, Nonsense and Impracticalities.” Martial Arts Training. November, 1998: 37.

[5] Lowry, Dave. “The Three Basic Concepts of ‘The Warrior Ways’.” Black Belt. July, 1997: 22.

[6] Wordsworth, Byron. “Unbeatable Forms.” Martial Arts Training. March, 1998: 6-12.

[7] Vargo, Keith. “The Myth of Street Fighting.” Black Belt. January, 1999: 26.

Monday, July 10, 2006

The Concept of Kiai

Please forgive the pervasive reference to Japanese and karate. Most of my references were written from the perspective of a karate practitioner and it helped the article's flow to stick with it.

In tournament competition there are often competitors “whose voiced kiai sounds like the squawking of a jungle bird with its tail feathers caught in a trash compactor.” [1] This type of banshee-like screaming does not accurately depict the true meaning of kiai. While the word “kiai” (pronounced key-eye) consists of the Japanese characters “ki”, meaning “energy”, and “ai” meaning “meeting” or “joining”, a definition of kiai to mean “a joining of energy” is not entirely accurate. Kiai (or “kiyap” in Korean) can be thought of as one’s entire mental state while focused during an action. “A true kiai can be completely without sound; this is an idea that more advanced karateka should consider carefully.” [1]

Many martial arts instructors insist on hearing students’ kiai, and though they might get a yell, they are probably not getting a kiai. This attitude is especially pervasive in children’s classes where the goal doesn’t seem to be performing effective techniques, but the volume at which the child can yell while performing them. More often than not, in these cases, the kids begin to focus more on the yell than the technique the kiai is supposed to reinforce

This attitude extends further when considering that many tournament forms are nothing more than a series of yells without any of the focus to back it up. This is not to say that tournament competitors are not focused, clearly they are. However their focus is not on the effectiveness of their technique, rather it is on how they look in performance of it. Christine Bannon-Rodrigues suggests that competitors “don’t forget to kiai. It not only draws attention to you, it makes your attack look stronger than your opponent’s.” [2] This reinforces the statement that competitors worry more about how they look than the actual quality of their technique.

For a kiai to be effective it must originate from the student’s ki and be timed properly as to induce a moment of distraction in their opponent. A series of high-pitched squawks will not accomplish this goal, and is more likely to interfere with the student’s breathing rather than the opponent’s concentration.

---------------------

[1] Lowry, Dave. “The Baffling Concept of Kiai.” Black Belt. January, 1999: 22.

[2] Banon-Rodrigues, Christine. “Popularity Doesn’t Count.” Martial Arts Training. May, 1996: 24.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

Getting There

Taekwondo tul (forms) are not just a series of poses with little or no importance placed on the transition between them. Whether your technique is effective is as much a function (if not more) of the transition than the final state. Consider a head block: Most beginners can tell you about where your hand goes, the angle of your arm, the distance from your head, etc. That's only part of the story, though. If a fist is coming straight at your face, it'll do you no good to end up in a perfect pose if your "block" swings up from the side and doesn't deflect the punch.

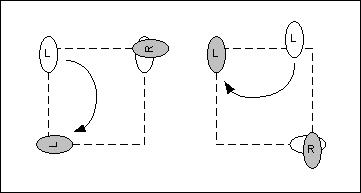

The same concept applies to stances. How you transition from one stance to the next can have a profound impact on the amount of power you can put into your technique. Let's take two common examples: The very first move of Chon-Ji tul and the common shift from back ("L") stance to front ("walking") stance. These are shown below.

The left and right feet are marked with an "L" and "R" respectively and the filled-in feet are the final positions. The dotted box is a square the length of your shoulder width on each side. In the left example, the left foot moves in a little and then back out to a proper front stance. The right foot merely pivots on the ball. The right example is similar; the left (front) foot moves and the right (back) foot pivots. Why?

Power, in the martial arts sense, is a function of momentum. When you move your front foot, your weight is momentarily supported entirely by your back foot. When you drop your weight into your stance and technique, it is going forward and contributing to the power of your technique. If you move your back foot, then your weight (and power) is going backward. Of course, if you move both feet, then the majority of your weight is going straight down.

It can take decades to perfect the little nuances of movement and timing that lead to power, but you'll be starting out in a hole if you don't transition from one stance to the next properly. The next time you practice your forms consider how you move your feet, because getting there is half the power.

Monday, June 05, 2006

Belt Promotions

Having been around Grandmaster Choi long enough to earn the rank I have has, if anything, only reinforced how much I still have to learn. (Grandmaster Choi was promoted to EIGHTH-degree black belt by General Choi Hong Hi, the founder of Taekwondo, 25 years ago!) Each rank promotion seems to be like a step closer to the edge of a deep valley; it only serves to show that it is actually deeper than you previously thought!

The most important thing I learn in Taekwondo is respect, and it is obvious why the higher-ranked students at the school seem to have the most of it. Grandmaster Choi's valley of knowledge is VERY deep and it is those of us who are closest to the edge who have the best appreciation for that depth. Whether I'll ever make it to the bottom of that valley is too much for me to consider, but that's not the point. The point is knowing that there's always going to be something deeper to learn and that's what keeps me going back!

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

Eclectic Martial Arts

Taekwondo and Isshinryu are very similar and very different. TKD achieves power by dropping your weight into a technique. The adjustment from rotating my hips was difficult. Now I probably do a combination of both, and my punches are pretty strong if I do say so myself... I wouldn't say that I consciously blend Isshinryu with TKD, but it probably happens anyway. I also trained in muay Thai when I was an intern in Arizona (summer/fall 1995) and that also had a profound impact on how I punch. I don't think it's possible to train in any style for a significant amount of time (which varies from style-to-style and person-to-person) and not have your technique affected by it. It's like an intimate relationship: No matter how long it was, you're a different person because of it...

Grandmaster Choi trained under General Choi Hong Hi, the founder of Taekwondo. To call him "traditional" would be an understatement. There aren't many 72-year old grandmasters who still run their own school and teach six days per week, but Grandmaster Choi does. He has many fourth- and fifth-degree black belts, a sixth-degree and seventh-degree black belt who are his students. They don't run their own schools and show up occasionally, they're in class just like the white belts. Most of them take private lessons due to their schedules and the more advanced techniques he teaches high black belts, but he's still the teacher and they're the student.

I don't necessarily agree that teaching eclectic styles is a good thing. Too often people get a black belt and think that's it. They move on, maybe start a new style, open their own school, but never really take the time to explore the deeper aspects of the style. Eclectic styles tend to be very superficial. They supposedly take the "best" of this style and the "best" of that style, but all the instructor is doing is blending techniques they know and like. The "best" of any style is something those instructors may never have learned because they didn't stick around long enough to learn it.

I think that as a student it's not a bad thing to incorporate other styles into your "arsenal." Like I wrote earlier, my muay Thai training taught me a lot about power, how to use my knees and elbows, and how to block a low kick with my lead leg. I do those leg blocks in sparring, but when I throw a roundhouse kick in one of my TKD forms it looks like a TKD roundhouse kick, not a muay Thai roundhouse kick. Your arsenal should always have one style that is your main style, chosen through careful consideration of what works for you. If my arsenal were a bouquet of flowers, there would be a dozen red roses (because I like red roses best) with some other nice flowers in for a change of color and to complement the roses. The roses are TKD and the other flowers are the other styles in which I've trained. I wouldn't try to create a new flower that is a cross between them all because that would destroy the beauty of the individual flowers!

Monday, May 01, 2006

Location, Location, Location

What’s your location? If you’re doing a mid-section punch with your opponent facing you, you should locate your punch to strike the solar plexus. Why the solar plexus? Because striking the solar plexus will have the highest “pain ratio” in your favor. I define “pain ratio” as the pain inflicted on your opponent divided by the effort expended by you. This is an important concept! When I was training in Muay Thai, the pain ratio of those leg blocks was barely over 1.0. My instructor told me “It hurts more to kick a block than to block a kick” but in my experience, not much more.

I often see beginners either punching straight out from the shoulder or seeming to target the sternum. Why? The sternum is solid bone and anyone who reads Patricia Cromwell or Tess Garritsen novels will tell you it take a buzz saw to get through someone’s sternum during a post-mortem. When your opponent’s sternum and your meta-carpals collide, don’t expect to come out ahead! Some of you may be thinking, “No problem, I can break bricks with my hands!” Ignoring the fact that bone is a LOT stronger than your garden-variety capstone brick ($0.79 from Home Depot), why choose a target that has such a low pain ratio? That same punch to the solar plexus would be devastating! Lower your punch by four inches and increase your pain ratio ten-fold.

Now comes the hard part: practice. A good rule of thumb is to practice as if you’re striking someone your own height. If you’re really short (or just happen to be female), it might make sense to raise them a bit if you feel it’s unlikely you’ll be attacked by someone of similar stature. Martial arts techniques tend to describe the location of strikes in relative terms, meaning that a technique might be a “punch to the face” or a “kick to the ribs.” This is as opposed to absolute terms, which would be describing a kick as “five feet above the ground.” The key to good forms practice, then, is to create a mental image of your “opponent” (or opponents) and locate your strikes appropriately and consistently with respect to that imaginary opponent’s height. The idea is to train yourself to think about this sort of thing, not necessarily hard-wire a permanent location into your brain. You should be willing (and able) to vary the height of your imaginary opponent, and observers of your practice should notice the difference. Keep in mind that if you imagine yourself fighting Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (as Bruce Lee did in "Game of Death"), then it may be unrealistic to think you execute an effective kick to the head.

In my opinion, instructors should be less of a stickler about the height of a punch, but instead focus on consistency. If a student consistently punches above his/her own solar plexus, ask about the height of his/her imaginary opponent. If you get a reply of “huh?” then take the time to explain the “imaginary opponent” and “pain ratio” concepts. When students get in the habit of locating their strikes to high pain ratio targets on imaginary opponents during practice, their training will be more valuable in a self-defense situation.

Friday, April 21, 2006

Welcome to my blog!

I'm a third-degree black belt in Taekwondo under the instruction of Grand Master Sun Duk Choi, founder of the International Tae Kwon Do Institute and President of the Arizona Tae Kwon Do Association. For more information about Grand Master Choi, please visit the school's web site at http://www.aztaekwondo.com. For more information about me, please read on.

I started my martial arts training in 1991 as a student of Isshinryu Karate in Rochester, NY. When I moved to Arizona in 1996, I switched to Taekwondo mostly because there wasn't an Isshinryu school nearby but also because I was ready for a change. I'm glad I did! I love training in a real martial art with a real grand master! (Not so incidentally, I met my wife while training in TKD so it has changed my life in more ways than I can imagine!)

Next month, I'll be testing for fourth-degree black belt. While I won't make any predictions about whether I will pass the test, I will state this: Recently, I have started working more closely with colored belts (non-black belts) and have really enjoyed this aspect of my training.

My plan is to use this blog to share more of my thoughts than I normally get to share during a 90-minute class, or a five-minute one-on-one practice session. Ideally, I'll post about once per week. My hope is that Grand Master Choi's other students will gain some benefit from this additional knowledge-sharing, and that non-students will gain some insight into what training with a real grand master is like.

Enjoy!

Matt Jones